We often think of AI as a tool to predict the future—like guessing the weather, stock prices, or whether someone might get sick. But AI is starting to do something even more powerful: helping us understand the rules behind how complex systems work.

A recent issue of Complexity Thoughts explores this shift, showing how new AI methods are uncovering the hidden patterns behind things like disease spread, traffic flow, brain activity, and more. The goal isn't just to know what will happen—but to figure out why.

From Forecasting to Figuring Things Out

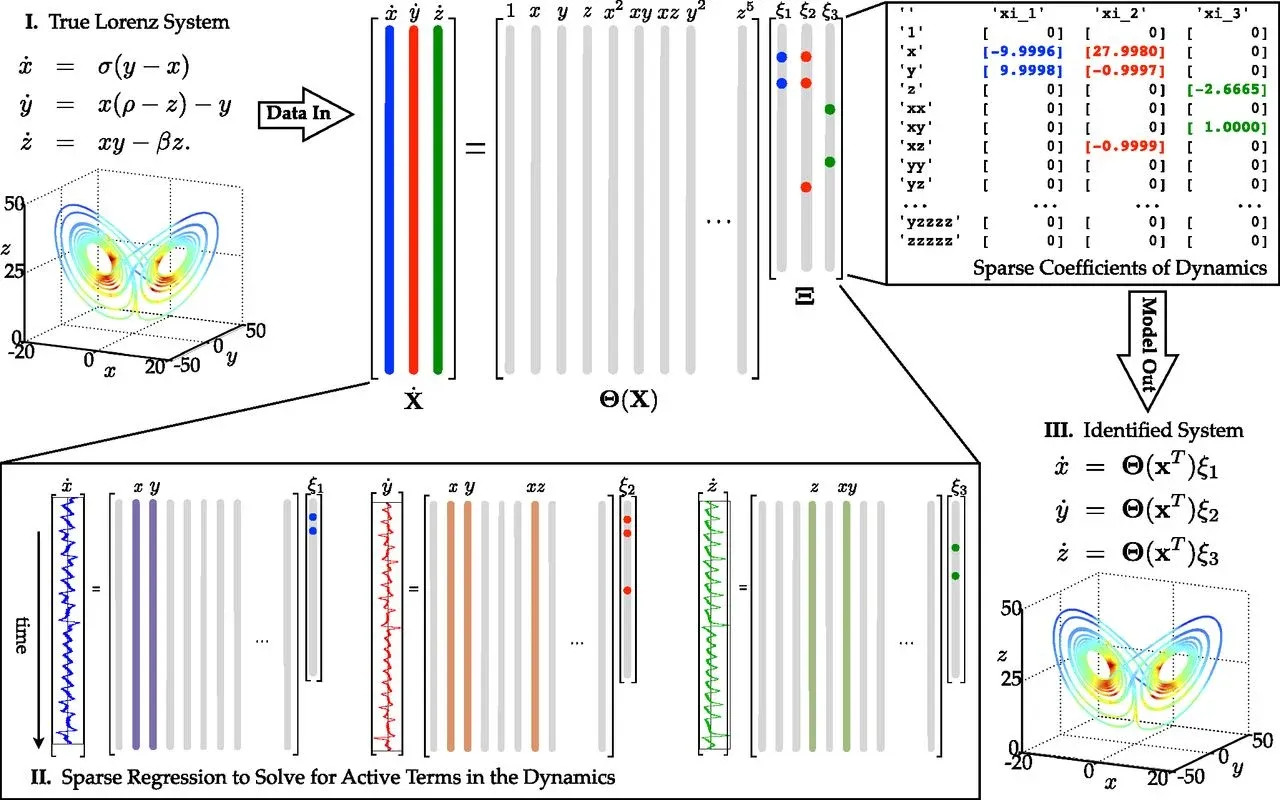

Most AI tools today are built to spot patterns and make forecasts. But these new approaches aim to find the actual equations—the basic rules that explain how a system behaves over time.

That’s a big leap. It means AI isn’t just guessing anymore—it’s helping build scientific models.

Why Simpler Models Are Better

Many of these studies use a method called sparse modeling. Instead of creating big, complicated equations, these models look for the smallest number of pieces needed to explain what’s going on.

Why? Because most systems—even complex ones—are driven by just a few key factors. If we can find those, we get models that are easier to understand and work with.

This approach is already being used to:

- Study how fluids flow,

- Track how diseases spread,

- Understand patterns in brain signals,

- And model chaotic systems like weather patterns.

Finding the Right Way to Look at a System

Sometimes, raw data is messy or overwhelming—like thousands of brain signals or climate measurements. Even with powerful tools, it’s hard to see what matters.

One AI method solves this by first learning the best way to describe the system, and then figuring out the rules. It’s like teaching a computer to choose the right map before trying to navigate a city.

A Machine That Thinks Like a Scientist

Another team built what they call a Bayesian machine scientist. Instead of trying one model, it tries out many different ones, tests how well they match the data, and picks the best. It even learns from a large library of past equations, the way a human scientist might rely on years of experience.

When Randomness Is Part of the System

Some systems—like bird flocks or the brain—are naturally unpredictable. They have a lot of randomness built in. Instead of treating that randomness as noise, a new method called a Langevin Graph Network includes it in the model.

This has already led to real discoveries:

- Showing how birds flock using rules scientists have long suspected.

- Modeling how harmful brain proteins spread—something important for Alzheimer’s research.

Why This Is a Big Deal

Together, these projects show a big shift in how we use AI:

- Not just to automate tasks, but to help us discover how the world works.

- Giving us simple, understandable models we can use to guide action.

- Making science faster, more open, and easier to explain.

In a world dealing with complex challenges—like climate change, pandemics, and social disruption—this kind of AI could help us not only respond faster, but understand better.

Want to explore more? Check out Complexity Thoughts for links and summaries of these fascinating papers.